Thérèse went on to tell Pauline how much she loved her. Every day, when she heard someone come in, she would always think that it was Pauline. When it was not Pauline a hint of sadness entered her soul. Thérèse saw her as the light that chased away the darkness. Pauline was the song that Thérèse’s soul sung loudly even without both of them ever having to say a word to each other. On September 24th, it was Thérèse’s anniversary of her veiling. Pauline received permission from the prioress to have a Mass said in her name. Later, Pauline went to see Thérèse but was met with disbelief. She saw that Thérèse’s symptoms did not change and was still causing her to suffer immensely. Thérèse caught on to Pauline’s grief and questioned her if she had the Mass said in her name to relieve her symptoms. Pauline told her that it was true and said, “It was for her own good”. (LC) Thérèse responded back by saying, “I must be the will of God that I suffer”. During Pauline and Thérèse’s conversation on the 26th of September, Thérèse was using a dead leaf, which was barely hanging from a tree by a spider’s web outside the window of the infirmary, to describe her life. Thérèse pointed to Pauline the dead leaf and said that it was the same way her life was now, hanging by a simple thread. On September 29th, Thérèse was in her final hours of suffering. The physical signs of her immediate death were more evident than ever. Pauline, as well as Marie and Céline sat by her at her bedside while Thérèse surrendered to her suffering. Pauline read to her about St. Michael the Archangel to help comfort her. However, Thérèse noticed that Pauline was suffering from one of her severe migraine headaches. She motioned to Pauline to go to her cell and lie down. Late in the evening, Pauline left the infirmary and went to an adjoining cell close to the infirmary. Marie and Céline stayed with Thérèse throughout the night. As morning rose, Pauline got up and left for the infirmary. She stayed with Thérèse while Mass was being held in the Chapel and tried to console her while she was battling periods of suffocation. Pauline told her how much she loved her and what a blessing she was to her throughout her life. Céline said to Thérèse that her last look should be on Pauline. But Thérèse wanted to offer it to Mother Marie de Gonzague out of respect. Thérèse said to Pauline do not be offended if I do not give you my last look. I want to give my last look to the person in need of it the most. As the hours progressed, Thérèse’s condition was at its worst. She could barely breathe and her skin was turning purple as well as large drops of sweat were pouring down her face. Pauline rushed out of the infirmary because it was overwhelming for her to see her sister suffer so much. She walked to the statues of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and Saint Margaret Mary and kneeled before both of them and pleaded to the Sacred Heart of Jesus and to Saint Margaret Mary to relieve her sister’s suffering. She then came back to the infirmary and prayed some more. The community was summoned twice to the infirmary. The first time was at five o’clock and it was thought that Thérèse would have a few more hours of life before she died. The prioress told the community that they may leave, but at seven o’clock, she reversed her decision and summoned them to come back. It was at this moment that the community witnessed Thérèse’s ascent to Heaven. As Thérèse held onto her crucifix, she whispered her last words of how much she loved God. She then went into a state of ecstasy and breathed one more time leaving her last look at her sister Céline at twenty minutes after seven. Minutes later, Pauline wrote a small note to Léonie, her uncle and aunt who were praying in the Carmelite chapel for Thérèse. A lay sister brought the note to them to let them know of her passing. Pauline, Marie and Céline would later speak directly to them in the reception area about Thérèse’s funeral. Once the community left the infirmary, Pauline walked out into the courtyard to retrieve the dead leaf with the spider’s web still intact. The dead leaf had fallen to the ground due to the force of the wind of the storm that had passed through at the time of Thérèse’s death. It was that same leaf which Thérèse had used to symbolize what her life was like on the 26th of September. Later that night Pauline, Marie and Sister Aimee of Jesus prepared Thérèse’s body for her funeral. Thérèse’s body was taken to the Carmelite chapel where the mourners could view her body. On October 4th, Thérèse’s funeral took place in the Carmelite chapel. After the ceremony was over, Léonie led the procession of mourners to the Lisieux cemetery. Thérèse was to be the first Carmelite nun to be buried on a plot of land at this cemetery, which was recently purchased by her uncle Isidore for the Carmelite nuns. To honor her sister Thérèse, and using her talents from years of painting miniatures, Pauline painted Thérèse’s name and anniversary dates on the cross that stood at the back of her grave. After Thérèse’s burial at the local cemetery, Léonie went to visit her sisters in the reception area at the Carmelite monastery. Pauline wanted to keep Thérèse’s clothing intact and asked her if she would purchase her clothing so that it would not be burned or given away to another sister. Unfortunately, Thérèse’s sandals were not spared and they were burned by mistake by another sister. Mother Marie de Gonzague allowed Léonie to buy the remaining articles of her clothing from the Carmelite monastery. Pauline’s next task to honor her sister’s memory was to get Thérèse’s autobiography published. A tradition of the Carmelite Order after the death of a nun was to have an obituary letter written and sent to each of the Carmelite Orders in France and also to Carmelite communities around the world. This was going to be no easy task for Pauline because there were many obstacles in her way. The manuscript that Thérèse wrote prior to her death was addressed to Pauline as well as to Marie. In order to calm Mother Marie de Gonzague’s sensitive nature and not offend her, Pauline erased her name as well as Marie’s from the manuscript. Pauline replaced the names with Mother Marie de Gonzague’s. Pauline was fearful that if Mother Marie were offended by what was written in the manuscript, she would burn it in the fire. Pauline took the manuscript to Mother Marie de Gonzague to be reviewed. After reading the manuscript, Mother Marie sought out Fr. Godfrey Madeline of the Norbertine Fathers at the Mondaye Abbey. On October 29, 1897, Pauline gave Fr. Godfrey Thérèse’s manuscript. After he reviewed the manuscript, he was immediately inclined to receive the Bishop’s permission (imprimatur). But after the Bishop read the manuscript, he refused to give the imprimatur that Fr. Godfrey was seeking to have it published. Fr. Godfrey went to see Pauline and asked her if she would allow him the opportunity to try again. She consented. Fr. Godfrey then took the manuscript to the Diocesan Office of Censorship. There they reviewed the manuscript to see whether or not it was in line with the Church’s teachings and it was. After Thérèse’s manuscript was reviewed, Fr. Godfrey made some recommendations. Some of his recommendations that he made were for Pauline to remove some sentences which he deemed to be “too intimate” for the general public as well as other sentences which he saw as being repetitious. He also titled the manuscript “The Story of a Soul” dividing them into chapters, which he felt, was needed prior to it being published. It was essential to have him review Thérèse’s manuscript as well as speak to the bishop so that they could get final approval for it be published. On March 8, 1898, Fr. Godfrey notified Mother Marie that he received permission (imprimatur) from the bishop for the book to be published. Once deemed by Thérèse as her “biographer”, Pauline made the recommended changes to Thérèse’s manuscript. Thérèse had told Pauline prior to her death that whatever changes that are made by her, would be the same as if she were to do them herself. She was also not to get upset or worried over the changes that she would make to the manuscript. Thérèse had also asked her to include in the manuscript about charity, God’s justice and having confidence in God. Pauline sought out to get her sister’s autobiography 'The Story of a Soul' published. She looked to her uncle Isidore to arranging the details of the publication of the autobiography with the publishers directly. She convinced Mother Marie de Gonzague to allow her to send out published books instead of sending an obituary letter to the other Carmelite monasteries. In October of 1898, Pauline had passed through her last obstacle with the publication of the autobiography. Pauline was finally able to honor her sister’s memory by sending to the other Carmelite monasteries the first published edition of the 'The Story of a Soul'. On January 28, 1899, Pauline’s sister Léonie once again made her fourth attempt at religious life. She entered the Visitation monastery in Caen. This time, as her sister Thérèse stated prior to her death to her other sisters that after her death, Léonie will remain there permanently. Léonie’s sisters were very excited about her entrance but were very cautious. Marie, Pauline and Céline all prayed for her and encouraged her through their letters. Pauline was given a brief opportunity to see Léonie in 1902. Pauline and Mother Marie de Gonzaga were traveling to a city called Valognes, located in the northwestern part of Normandy, on business. This was a special gift and blessing for Léonie because she thought she would never see any of her sisters ever again after she entered the Visitation monastery. This would be the only time for Pauline to see where Léonie lived and worked in what was described to her in the letters written by Léonie. It was time again to elect a new prioress. Mother Marie de Gonzague was the current prioress at the time that defeated Pauline by a very narrow margin in the last elections. Her sisters still considered Pauline as a good candidate for the position this time around. On April 19, 1902, the charter members of the monastery voted for the new prioress. Pauline received the most votes and once again became prioress. Pauline celebrated her feast day on January 21, 1903. A tradition of the Carmelite monastery was to give some form of gift to the nun who was celebrating their feast day with the community. One of Thérèse’s former postulants, Sister Marie of the Trinity, composed a book of the four gospels titled: 'History of the Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ.' Pauline was truly blessed by her beautiful gift. Mother Marie de Gonzague was diagnosed with tongue cancer in 1904. Her health dissipated rapidly and she was placed in the infirmary. Despite their differences, Pauline devoted a lot of her time taking care of Mother Marie at her bedside. On December 17th, she looked up at Pauline and said, “I have offended God more than anyone else in the community. I should not hope to be saved if I did not have my little Thérèse to intercede for me.” (WWM) Pauline, along with her Carmelite sisters kneeled at her bedside and witnessed her death. Her funeral was conducted in the Carmelite Chapel and she was buried in the Lisieux cemetery. Sister Marie of the Eucharist was Pauline’s first cousin. She, too, had entered the Carmelite monastery of Lisieux in 1895. All of the Martin sisters were very close to the Guérin family especially after their father, Louis Martin, died. Sadly, in 1905, the doctor who examined Sister Marie revealed the fatal news to Pauline. She had tuberculosis. Like Pauline’s sister Thérèse, their cousin had contracted the same fatal disease; it was as if history was repeating itself yet again. This was the year where Pauline, Céline and Marie had to witness their beloved cousin waste away like their sister. Sister Marie of the Eucharist’s father, Isidore, and brother-in-law, Dr. La Neele, worked feverishly to find new medicines to cure her of her fatal illness. However, their valiant efforts failed. A novena of Masses were requested by Pauline to ask her sister Thérèse for intercession, which echoed through the doorways of the monastery. Days later, Thérèse responded to their prayers in a dream to one of her Carmelite sisters. In her dream, the Carmelite sister saw an image of Thérèse and she said to her, “If you hear my voice after Sister Marie of the Eucharist has died; you will know that her soul has ascended to Heaven.” Like their sister Thérèse, Pauline and her Carmelite sisters gathered around her at her bedside and witnessed Sister Marie of the Eucharist’s last agony as her soul ascended to Heaven. Immediately, after Sister Marie of the Eucharist’s soul ascended to Heaven, the same Carmelite sister heard Thérèse voice. She told her that Sister Marie was with her in Heaven forever. Her funeral was conducted in the Carmelite Chapel and she was buried in the Lisieux cemetery alongside Thérèse. With abundant interest and devotion in Pauline’s sister Thérèse, correspondence increased between those that were devoted to Thérèse and the Carmel of Lisieux as the years progressed. Many religious corresponded directly for guidance on Thérèse’s ‘Little Way’ from Pauline. It was impossible for Pauline to answer all of the letters that were received, which sometimes numbered in the hundreds each day. But, there was one devotee in particular that caught the eyes of Pauline. Her name was Sister Stanislaus of the Blessed Sacrament from the Carmelite monastery of Boston, who received one of the first editions of the book, 'The Story of a Soul.' She was deeply drawn to the ‘Little Way’. She started correspondence with Pauline and was periodically counseled, through letters, by her. Later, Sister Stanislaus would become one of the foundresses of a new Carmelite monastery in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America. Her devotion to Thérèse became so deep that her sisters knew her as the ‘Little Flower of Philadelphia.’ At that time, Sister Stanislaus’s monastery became the mid-point between the Carmelite monastery of Lisieux and America. The Carmelite monastery of Philadelphia supplied many of the intercession cards, pictures, as well as booklets of Thérèse to the American communities to promote her canonization. In 1907, Sister Stanislaus asked Pauline Wilcox if she would commission a portrait to be painted by Thérèse’s sister Céline. Pauline Wilcox also agreed and Céline painted a portrait of Thérèse. The portrait was sent to the Carmelite monastery of Philadelphia where it was venerated in a side chapel until 2002. To ensure the longevity of the portrait, it was sent as a donation to Blessed Pope John Paul II Shrine (formally known as the John Paul II Cultural Center) in Washington, D.C. It is now located in the chapel where many followers that come still venerate it today. In 1908, elections were held again for a new prioress. With increased interest in Thérèse from around the world, they needed a prioress that was very well rounded in leadership of the monastery as well as dealing with the public. Sister Marie-Ange of the Child Jesus was thought to be the right candidate for the position. Even though she was not a professed nun at the time she also could not vote in the elections. Sister Marie-Ange was the first to enter the Carmelite monastery after the death of Thérèse and attributed her entrance to Thérèse. She was very devoted to following Thérèse’s ‘Little Way.’ After the results were in, the community summoned her where they told her she was the new prioress. Sister Marie-Ange of the Child Jesus, now Mother Marie-Ange of the Child Jesus accepted this position gracefully. This became an opportune moment for the new prioress, on the first day of her leadership, to appeal to the new bishop, Bishop Thomas Paul Henri Lemonnier. Bishop Lèon Adolphe was appointed Coadjutor Archbishop of Paris, France in 1906. Bishop Thomas Paul Henri Lemonnier came to the monastery to welcome the new prioress, her first official action, was to request to him to officially open Thérèse’s cause for beatification. The Bishop agreed and soon after their meeting he started work on preparing for her cause. The process was officially opened in 1909. However, Mother Marie-Ange of the Child Jesus served as prioress only eighteen months. She died during her reign as prioress at the age of twenty-eight. The funeral was conducted in the Carmelite chapel and she was laid to rest in the Lisieux cemetery. After the untimely death of Mother Marie-Ange of the Child Jesus, Pauline resumed her role as prioress again. By this time, Pauline made extraordinary efforts to piece together all of the information about Thérèse’s life that was needed by Father Rodrigue, postulator of the cause in Rome and Father de Teil, vice postulator of the cause in Paris for her beatification. When 1910 arrived the process for Thérèse’s beatification process was in jeopardy. Father La Fontaine, secretary of the Congregation of Rites, was very skeptical about the favors and the cures that were received by many people who invoked Thérèse to intercess on their behalf. There was one in particular that he wanted to suppress and that was the miracle that happened to Mother Carmela in Gallipoli, Italy. Father La Fontaine sat down with Father de Teil and told him the only way that he would be convinced to proceed with Thérèse’s cause is that he, himself, would receive a rare favor from Thérèse. Father de Teil contacted Pauline in the first week of August and relayed to her the difficult situation that he was facing with Thérèse’s cause and asked her to pray for Father La Fontaine’s intentions. Without hesitation, Pauline honored Father de Teil’s request and prayed earnestly for Father La Fontaine’s intentions to be answered. Two days after Pauline prayed for Father La Fontaine’s intentions, her prayers were answered. He received the favor that he was asking for. In the first week of September, the Diocesan Tribunal ordered Thérèse’s remains to be unearthed from the Lisieux cemetery. On the 5th of September her remains were brought back to the Carmelite monastery so that they could be examined. On August 3rd, the Diocesan Tribunal started their investigation on the two different versions of Thérèse’s autobiographies. They fully examined both autobiographies as well as other documents and came to the conclusion that the corrections that were made did not distort Thérèse’s message, both versions were basically the same. The evidence also showed that Pauline did not try to make Thérèse more ‘saintly’ than what she really was. In order to provide proof of the treatment Thérèse received prior to her death from Mother Marie de Gonzague, Pauline and some of her other Carmelite sisters wrote a deposition describing some of the incidents between Mother Marie de Gonzague and Thérèse to support their claims. Many people outside of the Carmelite monastery criticized Pauline for making any corrections to Thérèse’s autobiography. What most people did not understand, at that time, was that the corrections were necessary in order for the first edition of the autobiography to be published. Pauline faced several obstacles that she had to overcome. One example was the obstacles of Thérèse’s autobiography, was the threat of it being burned by Mother Marie de Gonzague and also it being censured by the bishop. In another threat by someone outside of the monastery, was an attempt to blackmail them. The blackmailer made false claims about having information about Thérèse that would repudiate what was written in her autobiography. When the authorities confronted him, he had no proof to back up his claims. Prior to her death, Thérèse warned Pauline there would be several obstacles that would be in her path in order to get it published and she was right. The Diocesan Tribunal had completed their investigation and on the 5th of September they ordered Thérèse’s remains to be unearthed from the Lisieux cemetery. Her remains were brought back to the Carmelite monastery so that they could be fully examined. After seeing her sister’s remains unearthed, Pauline reflected back on the thirteen years after Thérèse’s death, she said, “This blessed child who wrote these heavenly pages is still in our midst. I can speak to her, see her and touch her.” (PT) With the inundation of letters, telegrams and personal visits from many followers of Thérèse from around the world, Pauline was overwhelmed. With a lot of work on Thérèse’s cause, as meticulous as she was in her work, she carried that same persona in her relationships with her Carmelite sisters. Pauline gathered enough energy to also give her Carmelite sisters the same endless support and affection as she gave to Thérèse’s cause. As one of her Carmelite sisters stated to Pauline, in one of her letters, she said: “I find you so merciful, that it seems to me that God could not be more so. Oh, how much I love you.” (MT) Marguerite-Marie became a postulant; she was the sister of Sister Marie of the Trinity, on August of 1911. The austere rule was too much for the postulant and as a result she left the monastery. Though she left, she continued her contact with Pauline. Pauline counseled her for years on helping her find her vocation. She recommended to Marguerite-Marie that she should enter the Visitation monastery in Caen instead. This was the same monastery that Pauline’s sister Léonie was residing in. Acting on the advice of Pauline, she decided to enter the Visitation monastery and took the name of Marguerite-Agnes. Agnes was added to her name to honor the one that helped her so much in finding her vocation. Sister Marguerite-Agnes found herself also under the watchful guidance of Léonie as she took the necessary steps towards her profession. At the start of 1913 there were increased visits from the hierarchical of the church. Many of them were priests, bishops and cardinals; Thérèse’s message of the ‘Little Way’ was gaining more popularity among them. Some of them who requested to enter the Carmelite monastery wanted to be able to see and to pray in Thérèse’s cell and to meet Thérèse’s sisters Pauline, Marie and Céline. Most notably were many future popes and some currently having their own causes up for sainthood. Among the popes that are currently up for sainthood are Pope Venerable Pius XII, Blessed Pope John XXIII and Blessed Pope John Paul II. As 1914 approached, the threat of war was eminent. As World War I started, it had major effect on the Carmelite community as well as the Visitation community in Caen where Léonie was a professed nun. The Germans advanced into France through Belgium’s border and occupied the northeastern half of the country. Even though during this time, Pauline, her sisters at the Carmel and Léonie were miles away from the front lines, all of them were asked to make many sacrifices for the war effort. Food was rationed for everyone as well as medicines and other much needed supplies. The majority of the supplies were sent to the front lines for the support of the French soldiers. Léonie wrote to her sisters Marie, Pauline, and Céline because she was very concerned about their health and safety at the Carmelite monastery due to the rationing of supplies. Pauline, Marie, Céline all reassured Léonie that they were all right. Surprisingly, the number of letters received by the Carmelite monastery was not affected as much as it was thought to be because of the war instead the letters only increased. When the war came to the end, all of them survived the horrors. The canonization process for Thérèse progressed rapidly on April 9, 1915. A second examination of Thérèse’s virtues was required for the Apostolic Process. The examination of these virtues would take place at the Carmelite monastery in Lisieux. To the great joy of Pauline, Marie, and Céline, Léonie and her Mother Superior Jeanne-Marguerite traveled to the Carmelite monastery. Pauline had not seen her sister Léonie in thirteen years. It was an exciting eight days for all of the Martin sisters. They were blessed to be able to see each other again. It was a great joy for Léonie to finally see where her sister Thérèse lived and worked. Léonie remarked: “As we were sitting down together on the steps of Carmel, it was like nothing had changed. It was as if we were together at Les Buissonnets once more.” The examination of Thérèse’s sisters was over and it was time for Léonie to depart the Carmelite monastery. Pauline, Marie and Céline yet again, had to say their goodbyes to their sister Léonie. This time it was to be forever until they all saw each other again in Heaven. The Carmelite sisters arranged a song for Léonie’s departure, which was a very touching gift for her to receive. Many prioresses and mother superiors who followed the life of Thérèse sought out Pauline and looked upon her for her guidance on issues that they themselves were facing. Many of the religious were simply asking for prayers for their intentions to be prayed for by Pauline and her Carmelite sisters. Once example was in the early 1920’s when Blessed Mother Mary Ellerker of the Blessed Sacrament, a mother superior born in Handsworth, England visited Lisieux. She had a great devotion to Pauline’s sister Thérèse. She started her journey by touring the places she read about in Thérèse’s autobiography. Mother Mary then went to the Carmelite Chapel to seek out many graces from Thérèse. She brought with her many intentions but there was one in particular and that was for Thérèse to protect her communities. She relayed this same message to a sister in the reception area of the Lisieux Carmel when she went to visit them. The sister relayed the message from Mother Mary Ellerker to Pauline which in turn she asked the entire community to pray for Mother Mary’s intentions and to let her see God’s will for her and her communities. On May 31, 1923, Pauline was still prioress and received an unexpected honor from Pope Pius XI that she remains prioress for life. When Pauline heard the announcement in the Carmelite Chapel from Cardinal Vico, who was visiting the Carmelite monastery, she was immediately shocked by the announcement because she did not ever expect to receive such a high honor. Her first instinct was to refuse this honor because as she saw it she was not worthy of it but Cardinal Vico convinced her otherwise as she stated with great humility: “Be it done as the Holy Father wishes. I am a Carmelite and I will obey.” (CWe). Fr. Daniel Brottier, now declared blessed by the Catholic Church, wrote to Pauline in November of 1923. He was the newly appointed director of the congregation of Holy Spirit Fathers and a faithful devotee of Thérèse. He wanted to build a chapel in honor of Thérèse and wanted a sign of 10,000 francs from her so that he knew that this was God’s will for him. Fr. Brottier contacted Pauline and asked her if she and her Carmelite sisters would pray a novena to Thérèse for 10,000 francs to build the chapel. Pauline agreed and instructed her sisters to pray for his intentions. On the last day of the novena, said by Pauline and her Carmelite sisters, Fr. Brottier received his 10,000 francs for the new chapel. When Father Dolan visited the Carmelite monastery of Lisieux and the Visitation monastery of Caen in 1924, he came there to gain more information about Thérèse through her sisters. His first visit was to the Carmelite monastery where he spoke to Pauline, Marie, and Céline. During his conversation with Pauline, he asked her if she would give him a message from her to give to the followers of the Little Flower Society in America. Pauline agreed to his requested. She stated to Fr. Dolan that if the women of the society seek to honor Thérèse and be rewarded by her, they should consider dressing modestly and not wear anything that would be deemed by society standards as indecent. Pauline also added a message for the men of the society stating that if they seek to honor Thérèse and be rewarded by her, they must place themselves above everything that is not in line with the teachings of the Catholic Church. They should also make every attempt to receive Holy Communion as frequently as possible. After their conversations, he was left with the deep impression that the sisters were very holy, especially after the conversations he had with Pauline. When Fr. Dolan spoke to other people that were associated with the monastery, he asked them whether they too felt that Pauline was very holy. Fr. Dolan was introduced to Sister Agatha who was a frequent visitor to the monastery. She came there to assist the Carmelite infirmarian in the rehabilitation efforts of some of the Carmelite sisters. When Fr. Dolan asked her if she too felt that Pauline was very holy, she replied: “Pauline is the holiest because she formed the character of the Little Flower and therefore must be holy.” (CWb) Written by: R. Hann Bibliography Abbé Combes, ed. Collected Letters Of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux . (CL) New York: Sheed & Ward, 1949. Dolan, Albert H. Rev.. Collected Little Flower Works. Chicago: Carmelite Press, 1929. (CW) ---. Life of the Little Flower (CWa) ---. Living Sisters of the Little Flower (CWb) ---. Our Sister is in Heaven (CWc) ---. Where the Little Flower seems nearest (CWd) ---. The Little Flower’s Mother. Chicago: Carmelite Press, 1929. (CWe) ---. An Hour with the Little Flower (CWf) ---. God Made The Violet Too: Life of Léonie, Sister of St. Thérèse. (GV) Chicago: Carmelite Press, 1948. Piat, Stéphanie Fr. The Story Of A Family: The Home of St. Thérèse of Lisieux. (SF) Trans: Benedictine of Stanbrook Abbey. Rockford, Ill.: Tan Books and Publishers, Inc., 1948. Baudouin-Croix, Marie. Léonie Martin : A Difficult Life. (LM) Dublin : Veritas Publications, 1993. Beevers, John, trans. The Autobiography of St. Thérèse of Lisieux: Story of a Soul. (SS) New York: Doubleday, 1957. Clarke, John, trans. St.Thérèse of Lisieux: Her Last Conversations. (LC) Washington, D.C.: ICS Publications, 1977. Martin, Celine. My Sister St.Thérèse Trans: The Carmelite Sisters of New York. (MST) Rockford, Ill.: Tan Books and Publishers, Inc., 1959. Martin, Celine. The Mother of the Little Flower Trans: Fr. Michael Collins, S.M.A. (ML) Rockford, Ill.: Tan Books and Publishers, Inc. 1957 Mother Agnes of Jesus. Marie, Sister of St. Thérèse. Ed. Rev. Albert H. Dolan, O.Carm. Chicago: Carmelite Press, 1943. (M) Piat, Stéphanie Fr. The Story Of A Family: The Home of St. Thérèse of Lisieux. (SF) Trans: Benedictine of Stanbrook Abbey. Rockford, Ill.: Tan Books and Publishers, Inc., 1948. ---. CÉLINE: Sister Geneviève of the Holy Face. Trans: The Carmelite Sisters of the Eucharist of Colchester, Conn. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1997. © Redmond, Paulinus Rev. Louis and Zélie Martin: The Seed and The Root of the Little Flower London: Quiller Press Limited, 1995. (SR) Rohrbach, Peter-Thomas, O.C.D. The Search for St. Therese (SST) Garden City, New York: Hanover House, 1961 Martin, Pauline. Little Counsels of Mother Agnes of Jesus, O.C.D. (LCM) Lisieux, France, Office Central de Lisieux- distributed by Carmelite Monastery of Ada, Michigan Helmuth Nils Loose, Pierre Descouvemont. Thérèse and Lisieux (TOL) Trans: Salvatore Sciurba, O.C.D. and Louise Pambrun, Grand Rapids, Michigan Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1996 Gibbons, James Cardinal. Holy Bible (Douay-Rheims) 1899 Edition. (B) Baronius Press Unlimited, London, United Kingdom, 2005 |

Holy Cards

Prayers

Booklets

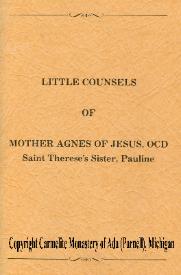

| For information on receiving a copy of the booklet: "Little Counsels of Mother Agnes of Jesus, O.C.D" Please click on the booklet |

Devotion

Prayer Petition

| Sub Directory |

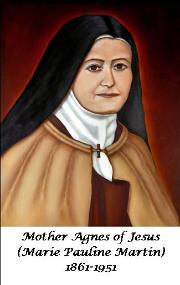

| Mother Agnes of Jesus Marie Pauline Martin "The Pearl of Lisieux" |

| Page IV |

Directory

Copyright © 2005-21 by r hann All Rights Reserved

Start of StatCounter Code -->

Martin Sisters

Multimedia

Connections

Communications

| Sub Directory |

| Mother Agnes of Jesus |

| © Carmel of Lisieux and Office Central of Lisieux |

| "The Pearl of Lisieux" |

| Eric Gaba (Wikimedia Commons user: Sting) |

Born:

Country:

Providence:

County:

City:

Died:

Country:

Providence:

County:

City:

Venerated at:

First Holy

Communion:

Entrance

into the monastery:

Patronage:

Country:

Providence:

County:

City:

Died:

Country:

Providence:

County:

City:

Venerated at:

First Holy

Communion:

Entrance

into the monastery:

Patronage:

September 7, 1861

France

Lower Normandy

Orne

Alençon

July 28, 1951

France

Lower Normandy

Calvados

Lisieux

Carmelite Monastery

in Lisieux

July 2, 1874

The Visitation Chapel at

the Visitation monastery

in Le Mans

October 2, 1882

Carmelite Monastery in

Lisieux

Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Beta-Mannosidosis

Bone Cancer

Chronic Myeloid

Leukemia

Cystic Fibrosis

Farber Disease

Gaucher Disease

Hunter's Syndrome

Lung Cancer

Maroteaux-Lamy

Syndrome (MPS)

Morquio A Disease

(PPMPS 1 VA)

Multiple Sclerosis (MD)

Pompe Disease

Reflex Sympathetic

Dystrophy Syndrome

(RSDS)

Schizophrenia

Seborrheic Dermatitis

France

Lower Normandy

Orne

Alençon

July 28, 1951

France

Lower Normandy

Calvados

Lisieux

Carmelite Monastery

in Lisieux

July 2, 1874

The Visitation Chapel at

the Visitation monastery

in Le Mans

October 2, 1882

Carmelite Monastery in

Lisieux

Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Beta-Mannosidosis

Bone Cancer

Chronic Myeloid

Leukemia

Cystic Fibrosis

Farber Disease

Gaucher Disease

Hunter's Syndrome

Lung Cancer

Maroteaux-Lamy

Syndrome (MPS)

Morquio A Disease

(PPMPS 1 VA)

Multiple Sclerosis (MD)

Pompe Disease

Reflex Sympathetic

Dystrophy Syndrome

(RSDS)

Schizophrenia

Seborrheic Dermatitis

| Download Centre |

| "Let us think of Jesus only! Jesus! Oh, let us have only His Name and memory on our lips and in our hearts!" - Mother Agnes of Jesus |

Booklets

| For information on receiving a copy of the booklet: "Mother Agnes of Jesus" Please send us your request in the Holy Cards Section and place in the comments section "Mother Agnes of Jesus booklet" to receive a free copy |

FAST TRAC

Websites

| Receive yours today! >> |

| Add yours Today! >> |

| In Need of a Prayer? >> |